.

.

Article Your Faith

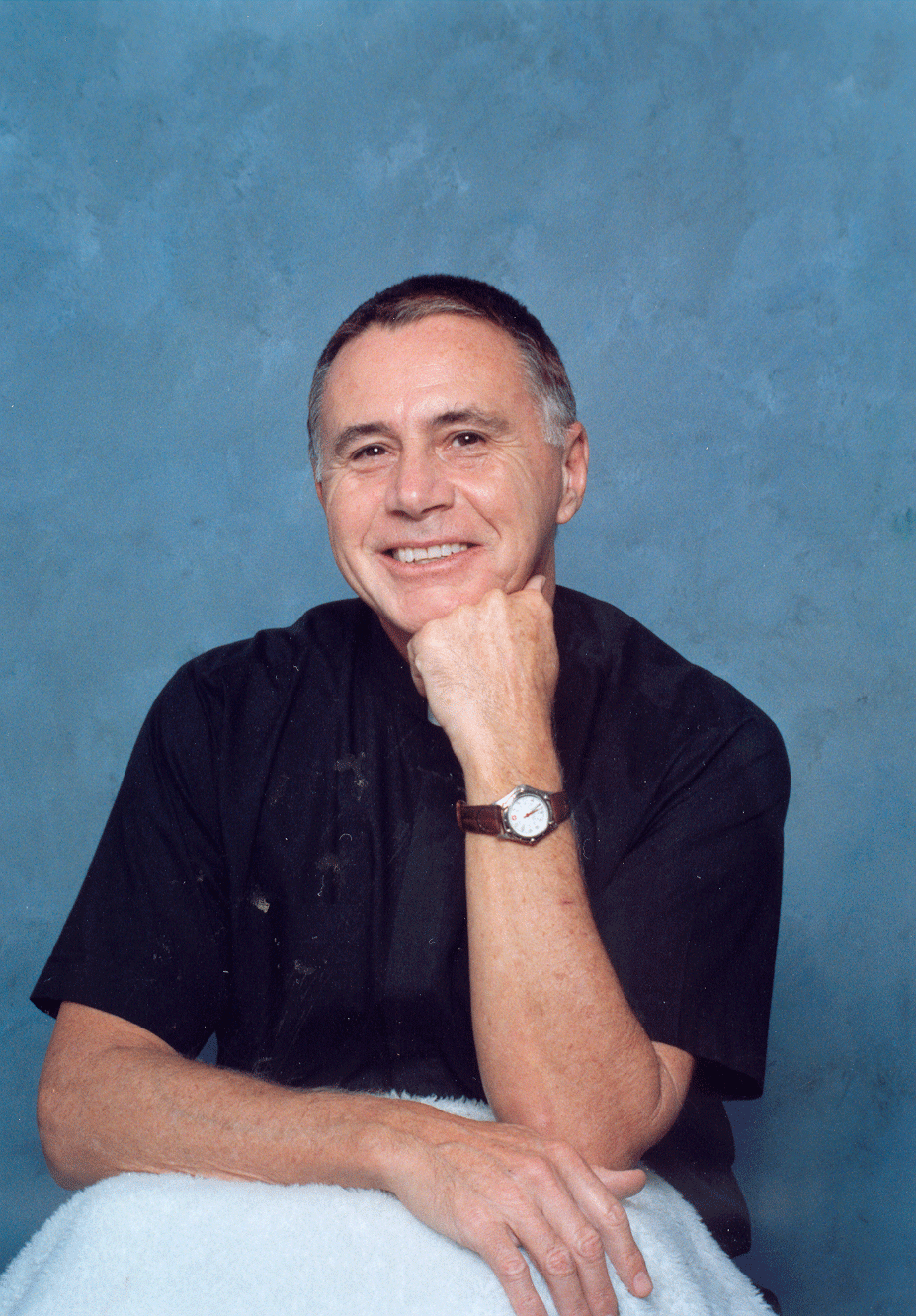

Robert Orsi makes a brave choice in his recent book Between

Heaven and Earth (Princeton University Press). “There’s a taboo associated

with speaking out of personal experience in your academic work,” Orsi, a

professor at Northwestern University, says. But Orsi ignores this taboo; his

text interweaves historical scholarship on Catholic devotions with

autobiographical anecdotes about his own Italian Catholic background. For

Orsi, then, the academic and the personal are intertwined and inseparable.

Much of Orsi’s work focuses on the study of

devotionalism—the personal relationships between humans and saints. But he

cautions against reading his academic work as a defense of the practice or

making assumptions about his own faith life.

You can be religiously observant and believe passionately

in LGBT justice. On the other hand, you can fervently work toward ending

abortion and barely attend Mass. While you might look at a Catholic academic

like Orsi and think you know what he stands for, internal faith lives are

much more complicated than stereotypes.

When you have an academic career that spans more than 25

years, it’s easy for people to put you and your ideas in a box. “I’ve become

the spokesman for not rejecting devotions as an integral part of Catholic

history, whatever one might think about them,” Orsi explains. “But I would have

felt unhappy if I had looked at my ideas today and I hadn’t changed over time.”

A lot of your work has focused on individual

relationships rather than theology or religious history as a whole. Why is

this?

People are formed in a web of relationships. And it’s in that

web where their ideas about religion and the way they inhabit the world come

together in a very direct and intimate way.

It brings us right into history’s beating heart to look

at family life in this way. For example, I tell my students that if you want to

understand why a suicide bomber does what he or she does, it’s not sufficient,

or even probably helpful, to only look at ideology or theology.

This is a very extravagant example, but it’s more

important to look at peoples’ lives. To look at what their uncle said to them

during childhood, what family stories circulated back then, and what stories

they were raised on.

We’re born into stories that are already under way. We

become part of these stories and taken up into those stories, and that’s the

ground on which we become who we are.

Look at Catholicism. Everywhere you look, it’s about

relationships; relationships in parishes, relationships with priests and nuns.

We come to be who we are in networks of relationships that precede us.

How do personal stories help us understand the story of

Catholicism?

I had an uncle who had cerebral palsy. I realized,

after coming across a devotion to Margaret of Castello in my research, that my

uncle had a very strong devotion to Blessed Margaret.

I began to use my own family as an archive for what I

wanted to do. My own intellectual work is so deeply rooted in the environment

from which I came and about which I have spent so much time thinking, that I

think it adds a necessary dimension to my theoretical and historical work to

bring that forth.

There’s an us/them structure in so much scholarship

on religion. The idea that “they” are out there, religious people, and

they do these things, and we—the scholars—study them. That always seemed

ethically, politically, and intellectually suspect to me and increasingly

untenable.

On the other hand, the historical and ethnographic

work that I do and my personal family stories inform each other. Not directly,

not in a sense of one supports the other—sometimes one undermines the other or

challenges the other or recontextualizes it in some way. But I always seek to

bring them into some productive, even if at times troubling, relationship.

Does the relationship between the personal and academic

play out in your own personal practice of Catholicism?

This is one of the other great tensions in Catholicism:

what happens in Rome on the level of the universal church in terms of theology,

liturgy, sacramental theology, and so forth, versus what happens locally or

individually.

Like all Catholic intellectuals, I sometimes envy Jews.

People have many different options for being Jewish. You can be radically

orthodox or radically liberal, and you have a whole spectrum where you can find

your community within that.

Speaking personally—a modern, Catholic, intellectual,

politically liberal scholar who is also intrigued by devotionalism and who

rarely lets a week go by without saying a rosary—where is there a place for a

person like me?

If I were Jewish, it would be the conservative movement.

Speaking purely as a Catholic and not as a scholar, I’ve sometimes thought that

it would be so great if there was an option like that. A place where you could

be politically left, but devotionally conservative. Like Dorothy Day was.

But where is this space, the space for thinking

about alternative ways of being Catholic, about asking yourself what you

believe?

Isn’t that “cafeteria Catholicism,” taking the pieces of

Catholicism that appeal to them and discarding the rest?

I never had any patience whatsoever with the contempt

that was heaped upon so-called cafeteria Catholics. It seems to me that

cafeteria Catholics are Catholics who are trying to make their way in a modern

world with the religious inheritance that they have; they have to figure out

how to be both authentically Catholic and, at the same time, true to their

other ways of being in the world. It’s very challenging.

Are there alternatives to “cafeteria Catholicism”?

I’m always amazed at my students. I’m always surprised at

the fluidity of their understandings of being Catholic.

They’ll say, for example, “I’m all for gay rights. I

think that is just really essential. But I’m a conservative Catholic.”

That’s fine to say, but I also think somehow that has to be raised to a level

of intellectual inquiry.

I don’t know why they can just blithely ignore the

tensions between what the church says and what they believe. I guess it has to

do with the phenomenon of John Paul II Catholicism. My students want to affirm

themselves as conservative Catholics, and yet, when you press them on

any of their beliefs, they’re completely not conservative Catholic.

Which is fine. I’m not calling for consistency. What I’m

asking for are spaces within the church, within the broad context of

Catholicism, where these questions can be hammered out without the thunderbolts

of either the right or the left falling down on us. We need a space where

Catholics can explore the tensions between religious and social views without

fear of condemnation and a sort of exile.

I also am pro gay rights. I have a gay child. But I’m

aware of the tensions that this creates with being a Catholic.

Why don’t young Catholics see a conflict between

these two beliefs?

I haven’t wanted to push them on this, but it’s a very

interesting question.

Sometimes I wonder if it’s simply a kind of Catholic

respectability issue. That this, in a way, is what it means to be a respectable

Catholic. It is thought that to be a Catholic is not to be out there advocating

for transgender issues, for example. In the same way that young people wear

certain clothes, they want to present themselves in a certain way.

It might also be that there’s no context for what

“conservative Catholic” means. It might also be that before Pope Francis there

was simply no way to be liberal and Catholic. It might have been the same kind

of protective covering that a Catholic in the 1970s would have used. “I’m a

liberal Catholic,” but then when you pressed them, you would have found much

more complexity than that name suggested. There was a certain kind of

protective covering. It might just be another way of saying, “Leave me alone.”

It’s a way of protecting yourself against having to think.

On a personal level, how do you deal with these tensions?

For me, this is the place to begin challenging and thinking

theologically and devotionally about how one lives with these tensions. How can

one work through these tensions as a contemporary Catholic?

But where is the space within Catholicism as a whole,

except perhaps at a few Catholic universities? Where can you actually do that?

How do you start to open up these spaces in the church?

Catholics on both sides, intolerant Catholics on both the

right and the left, contributed to creating a truly airless environment. Pope

Francis is doing a very good job within the constraints of a very difficult

position and within the constraints of a very problematic inheritance from his

predecessor.

I am hoping that one of the things that this pope is

doing is allowing for some circulation of air again where you can say, “You know

what? I’m politically left, but I say the rosary. I support gay rights, but I

also want to be a faithful Catholic.” He’s doing a very good job of trying to

pry open spaces where Catholics can be thinking Catholics again, without having

to fear what I’m calling the thunderbolts of condemnation.

But we still need to do more work. Where is the space

where these conversations can happen? How can we think theologically and

devotionally about these topics?

So things like supporting LGBT rights and preferring the

Latin Mass aren’t mutually exclusive.

Absolutely. They are not. They are not. The

question is, how do you come up with interesting combinations of those various

possibilities?

I’m speaking only as a personal Catholic and well outside

the organized church, but I think that in many ways the challenge for this

particular moment in Catholicism is how to think about different kinds of being

Catholic without the condemnation. From either the left or the right.

Is there a way to be able to say, without scaring all

your liberal Catholic friends, “Sometimes I’d really like to go to a Latin

Mass. That might be kind of cool,” without them immediately crashing down on

you, or some analogous thing on the other side?

This hasn’t been possible in the past?

The dialogue often becomes quite dark.There are often

thunderbolts of judgment coming from both the left and the right.

Think, for example, about women religious who have been

trying to have the conversation about their role in the wider church in

recent years. It’s been a very arid environment in which they were forced to

have that debate. They were always looking over their shoulders for the feared

judgment, trying to figure out who they were in relation to this church, being

confronted all the time by figures who were ready to condemn them.

That’s a very dark environment for the kind of open

exploration that I’m talking about. We shall see if there can be a lightening,

so that people who find themselves in the sort of position that we’re in can

actually work through these things without the thunderbolts.

I’ve spoken much more as a Catholic in this interview

than I thought I would. I don’t know what’s happening to me

.

What changed?

It might be these things have become clearer over time.

It may be that I’ve gotten older. I’ve been divorced and remarried. It’s hard

to see me as a traditional Catholic. And for many years, I was apprehensive to

be perceived too clearly as a Catholic.

In academia, any hint of my faith life was going to mean

that my scholarship was going to be viewed under a cloud of suspicion, I think.

That was the reality. Maybe it’s just that I don’t care anymore.

How do academics like yourself create this environment

within Catholicism that is open to more exploration?

Polls have empirically told us, “Look, Catholics in the

United States, at least, are holding a whole bunch of different and

contradictory understandings and practices.” But contentious Catholics on

either side don’t want to listen to what these empirical polls are saying.

So why not create an environment in which these

understandings and practices can be talked through and figured out, and

Catholics can make their way toward what they see and what the polls are

already telling us?

I can hear the voices of conservatism saying, “Yes, yes,

this is just modern self-indulgence. If you’re a true Catholic, you just obey

the church.” But I don’t think so. I mean, that’s a really good way to kill the

faith.

For many, many years I’ve lived my career without paying

a lot of attention to Rome. I mean, I like the city, and I go there all the

time. There are some great restaurants in Rome, and it’s a great place to be.

But whenever I begin a project, my first thought is not, “Well, let’s see what the

official Catholic teaching is.” In fact, it’s the opposite. Instead, I say,

“Let’s begin with people’s lived experience.”

When you’re a professor, then you often get asked the

question, “What exactly are you doing as a professor of Catholic studies?” There

are those who think that what professors of Catholic studies do is teach the

official teachings of the church. That would be a very sad and limiting

assignment for a professor. My role is to teach the lived diversity of the

faith as I see it in the past.

If people are exposed to how diverse the faith was in the

past, will spaces inevitably open up for diversity in the present?

On the level of Catholic studies, that’s a way to go:

Look at how Catholics have lived, look at the different ways that Catholics

have made lives for themselves.

I have also been surprised by how powerful the example of

the pope is. If you compare the atmosphere, which we are all capable of doing,

of the last two popes, it’s astonishing.

I suppose if one were a cynic, one could say, “Well, of

course. You know, Catholicism is an institution like every other institution,

and as the leader goes, so go all the sheep.” If you want your career advanced

within Catholicism under Benedict, you’re going to have to behave one way. If

you want your career advanced under Pope Francis, you’re going to behave in

another way. But it is pretty striking to me nonetheless how everything feels

different now and how quickly it shifted. I am stunned.

What was the shift?

When I first started teaching about lived religion and

devotionalism, people asked, “Why bother teaching that stuff? It has no

relevance.” In their minds, if you want to know about Catholic women, don’t

look at what women were doing when they prayed to St. Jude. Instead, look at

what the church teaches about women.

But if you listen to a lot of traditional Catholic

discussions or teachings of men and women, you’d think, “Have they ever

actually met a woman? Who is this? Who is this creature that they’re creating?”

John Paul II, may he rest in peace, was really indicative

of this tendency. You begin with an ideal of a woman, you define the ideal, and

then what happens in real life has to be accountable to the ideal.

The current atmosphere under Pope Francis could open the

way for a new empiricism. This could be a very healthy development where people

say, “Don’t give me idealized portraits of your mother transformed into a

theology of women. Instead, let’s look at what Catholic women are actually

doing and have been doing. Let’s look at what Catholic women have been doing

for centuries.”

Then, in the context of what we see empirically, then

let’s think about how we can understand Catholicism and women, Catholicism and

gender, or Catholicism and sexuality. Don’t give me some really idealized version

of Catholic sexual teaching. What are Catholics actually doing?

Do people realize that there are many different kinds of

Catholics?

I’m amazed how in every survey Catholics in the United

States come out liberal on every issue. You think, “Who are these

Catholics who are happily filling out these endless surveys?” But then, when

you look at the media, the only Catholics that seem to appear are not those

Catholics.

I’ve wondered whether or not there is the need in

American culture for Catholics to be a certain way. Catholics are expected to

be a certain way, and it’s very hard not to be that kind of Catholic,

given the serious cultural expectations. The New York Times would prefer

it, I think, if we were all another kind of Catholic.

They even do this with Francis, and I worry sometimes.

They’ve elevated him as this paragon of good Catholicism, and they’re going to

be very disappointed. And I think they’re going to be happy to be disappointed

when he does something that doesn’t conform to this image that they’ve created.

I tell my students that that’s what prejudice is: When

you think you know everything about a person because of one aspect of them

that’s visible to you, before that person even opens his or her mouth.

Whether they’re black or women or whatever, you think you

know what the story is with this person. I think with Catholics, it’s very much

like that in the United States. Certainly in academia: I know that the minute I

say “I’m Catholic,” a whole set of things fall into place that are not articulated

but are very strong.

If I say, “I’m a Catholic, but I really want to see space

for gay people to worship as full members of the community,” then they’ll say,

“You’re a bad Catholic.” They’re not even Catholics themselves, but they’re

happy to exile me from my own tradition. At that point, I stop behaving as a

Catholic they need me to be.

We have to be bad Catholics, obviously, always.

Is this set of cultural expectations new?

No, it goes back centuries, really. There’s always been,

floating around, normative construals of what a Catholic is.

It would be interesting to go back and come up with a

list of “bad Catholics” in history. We might find that they actually were very

interesting Catholics. I think what “bad Catholic” means is that, first of all,

these are Catholics who don’t conform to expectations that are imposed on them

either by Catholics or, very often, by non-Catholics. They don’t act the way

people want them to.

But these are Catholics who are really struggling to live

with the dual inheritance both of their faith and the world they live in. If we

were to come up with a list of bad Catholics, we might find that these were

some of the most interesting Catholics who have somehow gone unnoticed because

they fail to fit the standard stereotypes.

As we keep saying again and again, it’s in the places

where people don’t conform where the really interesting stuff is happening.